A letter on philosophy of mind, the problem of consciousness, and the mental-physical divide.

S.R.,

It was at about the tender age of seventeen that I was taken in by him. That I had found a sort of companionship in a man whom I had never met, yet who lived so close, and whose life intertwined with mine in very many unexpected ways. And even now in the several years since, and long after his death, I am still touched.

I have experienced, recently, a renaissance of myself, of that part of me that is fascinated by the physical world, and in particular the organisms that inhabit it. And I attribute this to Oliver Sacks, several of whose books I vowed one night to buy and read in a panic possessed, to see whether, and to prove perhaps that I was not, much like Plato did in going to Sicily, “full of hot air”.

I wrote to him the other night, though in vain, as he passed away, if I’m not mistaken, in 2015:

It feels disingenuous. It feels facetious. This part of me that delights in observations of the natural world. That it is forced by mimesis. That I am charmed by the transitions made by various organic compounds in the production of dopamine. That I am charmed by the evolved symbiosis of disparate organisms, like, say, figs and wasps, or beetles and magnolias. And yet I recognize that I have always been like this. Always interested in the world of sense, but always with the sense that vision itself was not sufficient, having a degree of unease with observation alone, taken, as it were, at first glance. It is a crude and inadequate knowledge we possess of the world down here, at least at the intersection of the sciences and their application, at least, I think, in medicine. It is only through theory, through speculation, I suppose, that the world takes breath, and only in activity that it breathes.

How insipid a world devoid of colour would be, and much in the same way how devoid of life would be the sciences–they should not even be called properly sciences without it–were it not for the provocation of thought. And yet it feels to me anyway that those of the sciences, and I know this can’t possibly be, are much like collectors of rare books, who steal away and hoard up anomalies or treasures–the observations and connections of the biologist are cloistered away in dusty storerooms all the same.

I remember that feeling of sitting in on biology lectures as an undergraduate, and feeling as if the information did not pertain, was gross and satirical, devoid of something, that I was alienated from a profoundly beautiful and miraculous reality, that the method was ineffectual, and in effect I was being restricted to the rote and tedious digestion of morsels with no satiety in sight.

You weren’t very far away, then, as I know now. It must have been only a matter of miles, if miles, or minutes, if minutes. And to think that I was once a younger man with uncomplicated intentions of medicine, and meaning, and engaged in your work, working out some meaning myself by intending to imitate you in yours. What a breath of fresh air to find a tactful humanism interlaced with an extensive repertoire of facts, observations, theories, speculations, and passions. And what a relief it is now to remember what I had forgotten–to have found again the world situated in its proper place, full, again, with wonder and mystery and unknowing.

But you were dead not long after I had found you. And if I had known, I would have written to you with these doubts, and criticisms, and wringing of hands. And if you were alive now I would write to you with the same doubts. And yet with a profound hope.

But now your books sit on my shelf, and I am alone.

You can imagine the abject horror that I have experienced in the wake of such a renaissance, forced to contend with being at the level of the natural world, and the mental gymnastic that I perform to assure myself that this is not all, that I am not reducible to my cerebral cortex, and that the vast swaths of the body which have been opaque to science will not, when we understand them better through the scientific lens, deal the death blow to metaphysics.

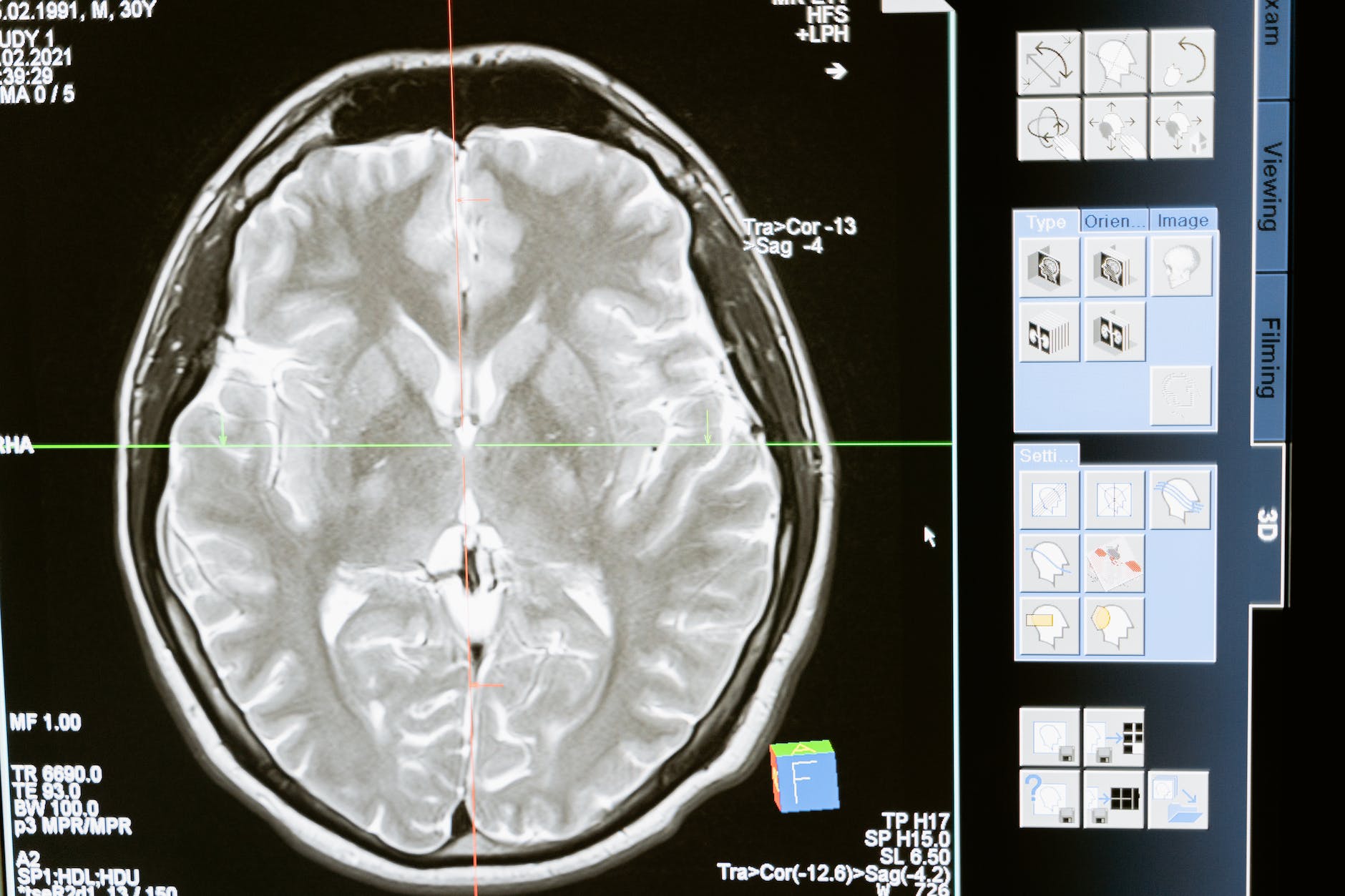

But this is all, of course, philosophic drama, though it does betray a very real anxiety on my part as to how to reconcile philosophy with science.We can take the hard problem of consciousness as one labyrinthine example. Is it the case that (human) consciousness is reducible to the nervous system? That brain states correspond to mental states has been shown well enough by the researcher, and is betrayed by our everyday experience.

Knock out, say, activity in a particular part of the occipital lobe (V4), and we become unable to experience colour, whether in our waking experience or in our memory. Knock out another section (V5) and we become unable to perceive motion (we become subject to a peculiar condition called “motion blindness”). Knock out a particular area in the temporal lobe and we become unable to understand language, another and we are unable to speak (Wernicke’s area and Broca’s area respectively). This much suggests that consciousness arises from, supervenes on, the activity of various cerebral and subcortical structures, that consciousness is the harmony of these structures, and is mediated by the communication between them–but we knew that much, and this is, of course, a very simple construction of this view.

And so, perhaps, we might find ourselves naked and explainable in light of recent and future breakthroughs in neuroscience, once we have discovered a theory of everything as per the brain–but whether these solve the hard problem of consciousness (the problem of qualia), I am not yet convinced. Perhaps it is not the biologist’s riddle, as he might be, ultimately, ill-equipped for the task.

In any case, if we were to approach the problem of qualia (the, “it feels like something to be anything at all”, problem) through this lens we might posit that the quale of my being a human being is informed by my particular nervous system, that the phenomenology of my emotions and my mental life is reducible to the host of unconscious processes that take place in my body, which ascend to ever higher parts of the nervous system, which give my mental flora and fauna their particular feeling, e.g., that anger is a sort of boiling or grating sensation might be explained by increased heart rate, blood pressure, and the release of cortisol into the bloodstream, at least in so far as my emotions are concerned. This correlation has been claimed by, namely, Antonio Damasio, in so far as the same areas of the brain which are responsible for perception of “internal” body states also show activity in the feeling of emotion (cf., Looking for Spinoza, p. 106), so that the phenomenology of the emotions directly correlates to how we feel in our own bodies.

This does not seem to explain a subtlety of the hard problem–that there is someone that I am who feels, and that this feeling takes place in the (poorly conceived) theatre of my mind, and that there is the feeling of the feeling subject at all. It is one thing to point to brain activity and heart rate, and yet another to say that consciousness is reducible to these (as some say), for brain activity is not feeling, much in the same way as sugar is not sweetness, nor its eating, its perception.

But, ultimately, this does not matter for our metaphysics.

We might retreat to the position of Berkeley, that all things are ideas in the mind, and while this is an option, while it is somewhat consoling, I find this somewhat unsatisfying, if irritatingly airtight (Berkeley did not believe in “matter” in our classical sense of the term as an invisible substrate in which qualities inhere, and in some sense he is right, preferring to encapsulate everything in the mind and its perceptions).

He might say of our neuroscience–“Well, that, too, is in the mind’s eye”.

My qualm, ultimately, is not so much that we are left with little ground to stand on, once we have explained away the consciousness problem in biological or physical terms, and with it the psychology problem, but that there are some who would reduce everything in the world to our current understanding of physics, trimming down our ontology of what things exist, in so far as we understand it in this sense of the physicist. But there is no reason to believe this–either the world is now exhaustively explained by physics (which it is not) or it will be (but is not now), but if it is not now, we cannot say, by physics, what does, or does not exist.

Science and philosophy are kindred projects, contra the crude, strawman physicalist (I am thinking in particular of the gigantomachia in Plato’s Sophist 246a-e).

But even if it were discovered tomorrow, I suppose, by some extraordinary and inexplicable means, that everything were “material” in some forgotten Greek sense, much as the Stoics conceived of the soul as a living animal within each of us (as per Arius Didymus), or as everything being fire and coming into and out of existence from fire, I would not be perturbed, as perhaps this world of ideas of which I am enamored, which is not present to our everyday sight, though it is as real as I am, or you are, is nothing more than a different disposition of matter, or activity at the quantum level.

It would do away with the hard problem, perhaps, to show that everything that is, as we might imagine, is, what it is, and perhaps that the mental is just another state of matter.

But maybe we would do well to say along with Isaac Asimov:

“What is mind? No matter.

What is matter? Never mind.”

Sincerely,

George